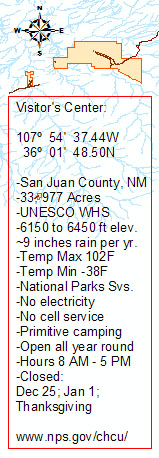

Dateline: 02 - 2010

This story actually started way back in 2003 at a remote protected area in Utah, called Hovenweep.

What we weren't prepared for were a scourge of gnats relentlessly swarming us early morning, and again regrouping for a late afternoon foray. These nearly invisible flying teeth left dozens of brutally itchy welts on ankle, wrist, hand and neck. Arriving back from our daylight recce of bizarre long abandoned ancient Anasazi cities with names the likes of Cutthroat Castle, Hackberry and Square Tower, ready to sit around the fire for the balance of the evening to write detailed observations of our visits, we were driven into our tent by the plagues.

Dunes and I discussed the inevitable: if we going to do serious explorations in this environment, and not getting any younger, we unavoidably would have to seriously consider some kind of mobile research abode with plenty of panoramic windowage, no-see-um screening and plenty of Thor to run our laptops, weather gauges, radios and reading light...

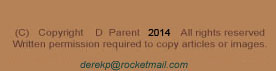

...fast-forward to 2005, we find ourselves stopped at the nexus of County Road 7900 and 7950 on the high-plains of New Mexico contemplating the next 16 miles of evil harsh back-country washboard, as convective blackness threatens a deluge. Well, we're safe in the brand new Silverado 2500HD 4x4 for the time being; and anyhow, we could just get out and duck into the high-tech Outfitter Caribou neatly clamped to the bed of the truck if things get out of hand with this micro-burst. There is comfort in knowing that if anything untoward should befall and bar our progress toward the Chaco Canyon, we could simply hibernate in the "high-tech" home, and wait it out; or kill an evening with heat, light and a hot supper via our marine battery power.

Digressing for a moment, just 2 days ago we had docked the Silverado at Outfitter Manufacturing, the outfit that had taken and ingested our myriad requests over a year ago, and translated all into our customized expedition camper. It seemed such a long and arduous journey from those first probing e-mails, growing all told to about 70 correspondences as the manufacturer applied and molded our requests into plus quam perfectum (see Silverdune's story at The Expedition to Pick up Campie). Leaving Outfitter late on delivery day, we made our way through heavy Denver traffic on the I25 down to Colorado Springs, where we spent our first night in sub-zero weather with the camper; by this juncture aptly named Campie. Testing all systems, including 3-way fridge, electrical systems, gas stovetop, roof lift mechanism, rooftop fan, stereo and vehicle charging system to Campie battery, we departed on a crystal-clear morning for Santa Fe, New Mexico; our Southwestern base for further excursions into Chaco and beyond.

It appears that the micro-burst isn't heading our way yet, says Dunes; Dunes being our teams esteemed climatologist. I agree, and suggest we get busy taping all our custom-made clear vinyl covers over the six ventilators disbursed around the Campie's exterior, and over the camper jack's open crank holes. I elect at this point to completely tape the perimeter of our rear door, too, and block all the weeping holes around our single-pane camper windows. I quickly deduced that Campie's rear wall aerodynamics wouldn't be conducive to a clean interior if even just a fraction of the red Chacoan dust could find its way around the perimeter door seals. So not wanting to test such a theory, on went the temporary Ductape. As you can guess, this custom cover Shtick wasn't the product of afterthought. No sir. Both Dunes and I had done a recon on the Chaco access drive several years before, noting the vast plumes of dust sticking like a magnet to the rears of vehicles gone by. With that scene in mind we quickly came to the realization that bringing any genre of RV through that kind of Saharan-like dust event could be potentially nasty for the workings of its various appliances; like the exposed fridge via outside vent for example.

All the sealing complete, conveniently a road grader slowly makes the turn onto 7950. Excellent! What a stroke of luck; we'll let the grader ramble on its way several miles, then we'll ride effortlessly over the new road surface sans washboard slowly never to catch up. Anyhow, the micro-burst storms appeared to be further off than previously calculated. The last thing we wanted was a wash-out and 400 pounds of slick red clay stuck under the truck like cement. Here we go, time to pull out.

Why would anyone in their right mind want to make high-plains crossing nearly 20-miles across some of the remotest, hottest, driest, windiest, least patrolled country in North America, anyway? The story is a long one. For Dunes it goes way back many years to the times she visited southern Arizona. Spending months of vacation in rented Blazer 4x4s crossing some of the remotest parts of Yuma, Pima, Santa Cruz and Cochise counties, soaking up the saguaro dotted vistas, hunting ancient ruins and rock art and doing research into the spread of disease across the desert landscape; for me it goes way back to my time in California. Taking mountain bike expeditions out into the Mojave Desert and Anza Borrego regions regularly, I knew these were the biomes I wanted to work in and travel through. With my background in mapping tropical protected areas, I developed a fondness for ancient Mayan civilization, its extent across Central America, it's art and architecture. With no formal training in Mayan studies, I found that applying my background in geographical spatial analysis to questions of Maya civilization I could better begin to understand this great civilization's rise and fall.

The question of visiting the Chaco region came down to the following: to delve into the largest most evident and complex abandoned ancient urban center ever discovered north of the Mexico border; to map the not so evident sites and graineries we may stumble upon while trekking the Chaco Culture National Historical Park (hereafter we'll call: CCNHP); to explore the extent of ancient Chacoan roadways criss-crossing the CCNHP; and to photo-catalog the rock art we have pre-determined that most interested us, looking for similarities with other more distant Anasazi site rock art. In the short time we will be visiting, it was obvious to us that we would simply be doing a cursory cataloging and observational expedition, however having Campie as a base camp would offer us comfort, and a place to sort the days photographs, write out observations, and over a hot supper and later fire discuss our findings.

We describe in some detail later in this expedition report some of the mapping and remote-sensing methods we use to derive our places of interest; places of interest to us include: ancient Puebloan roadway segments; potential ruin sites not yet excavated; and meridional orientations of select Chacoan Great Houses. Our objective in this piece is simply to show how and where we travel with our truck camper, and touch just the surface of our technical pre-preparations of electronic maps we use to further our knowledge of, in this case, the Chacoan civilization. In light of this, we will not feel slighted at all if you wish to skip over the technical details outlined thirteen paragraphs below. Additionally, this piece is not meant to be an academic paper on the Chacoan civilization. We are simply exercising our curiosity on this region by re-inventing the discovery wheel. Re-inventing because we have not acquired any electronic geographical archaeological data (GIS data) from past professional archaeological research to come up with our original map content! However, we have read myriad research papers on Chacoan road systems, and archaeological investigations on this region, and used paper text and paper-published maps as a general reference to ancient road systems and unexcavated sites, but have not attempted to scan and georeference any published ancient roads maps to show in our original content. The only exception to this was the use of the published Chacoan center place meridional coordinates (longitude coordinate from paper publication: Lekson (1999:113)), which I then generated the center place, Chaco Canyon in one of my GIS maps from. All road segments shown in our original map content were derived through our interpretation of remote-sensed products.

Any coincidental alignment with existing and confirmed and ground-truthed Chacoan roads GIS data from past research would be, how should I put this, greatly anticipated! In fact, any bona-fide researcher applying to us for a copy of our original GIS ancient roads data files (in NAD83) for the purposes of either confirming, disproving in any part or ground-truthing our ancient road segments identification effort will be happily obliged. Other data I use: our State, Federal, hydrological, remote-sensed and hypsographic (elevation) data comes from US repositories, for example the USGS, and are all in the public domain. Anyone receiving our ancient road segments datasets will be required to site us in any publication endeavor; whether publication is in electronic or paper format. Now with that out of the way, please enjoy our journey!

Starting out on the long stretch of R7950 was easy enough. We weren't in a race to get to Chaco; being before noon we had plenty of time to get there. I kept the speed at around 10 to 15 miles per hour (roughly the same speed as the road grader, now several miles ahead of us); we weren't kicking up much of a dust storm, in fact It was a bit disconcerting that the dust was following us off the port side for the first 20 minutes or so because of the diagonal winds. The first sign of Chaco we encountered was a Federal sign post indicating no vacancies. We were advised by relatives of mine (long time New Mexico residents) to completely ignore the sign, and to push ahead regardless. Well, nothing good comes to those who refuse to take won-ton risk we say! On we drive. It is evident that we were losing altitude as we headed towards Chaco. Our GPS was giving us 6883-feet elevation at our point of departure, and by around the 8-mile mark we had descended about 300-feet to 6550. We passed numerous offshoot tracks and what looked to be driveways (perhaps heading off towards remote Navajo hogans?), however the road to Chaco was as evident as an air landing strip cut out of the Amazon jungle.

The landscape along R7950 was comprised of low mesas with numerous sandstone and shale arroyos, with soapweed and fine-leaf yucca, flat and silver sagebrush, several goldenrod types, and wild buckwheat, but basically made up of high plateau scrubland. It's hard to believe that the area was part of an inland sea several millions of years ago. As a side thought, it is not uncommon to see rattlers crossing R7950 while driving when the sun climbs high enough to heat the ground up.

The sun was just about at peak by now, at about 12 miles into our drive over stretches of 500 to 600 feet of spine-rattling washboard gravel-- the grader having been left behind --we nose down an incline into the Chaco arroyo. If we'd been driving during heavy rains, this is the section of road we would be paying particular attention to: flash flooding occurs here all the time, so in addition to the warning road signage we make a mental note of the potential. We know from the Chaco wash that we are roughly a tad over 3 miles from the Chaco Culture National Historical Park boundary. So, at 15 miles per hour we should be at Chaco's park boundary in less than 15 minutes, with avoiding washboards and all- excellent! Campie seems to be taking the occasional washboard pounding well; the truck seems to be intact, no rattles and no flats yet.

This last stretch of road was fairly uneventful; now descending into a narrowing arroyo with taller scrub on either side just past the park boundary, to our tires and our surprise, we arrive at the park's beautifully paved road. What a shocker, a paved road way out here; say what? Anyhow, the truck and camper are thankful for the smooth ride after that bon-jarring 16 miles. 1.2 miles into the Chaco park boundary with canyon walls rising up about 100 or so feet on either side, we spot the park camping area on our right. The first thing on our agenda is finding our way into the campground and touring around to make note of appealing vacant site numbers. We find 3 vacant sites and high-tail it directly to the Visitor's Center to see which of these sites is truly vacant.

We secure one of the sites (the site we actually preferred the best; what luck) and pay for four nights. We're very happy with our site; it faces a shear sandstone mesa and is only 10 minutes walk to a near-by Anasazi ruin, located at the last campground loop at the base of the mesa.

Note: if you plan on attempting to camp at Chaco, it is important that you immediately on entering the park, bird-dog several vacant sites, and then get your body down to the Visitor's Center to cast your acquisition in stone (or, cash). This park fills up extremely quickly, so imagine having to drive all the way out to the gas station at the main highway, Farmington or Albuquerque to try again on another day! There is a small overflow RV parking, however it is inconvenient for washroom and water access.

We pull back into our site and set up a placer tent, fill it full of aluminum camping chairs, a light-weight aluminum folding table, and several foldable 5-gallon water containers; I removed all the vent vinyl covers and the tape around Campie's door, then drive the rig on a quick recon of the Park.

A 3 mile paved drive from our encampment put us beside the impressive ruin called Hungo Pavi, which we would guestimate to be about 350 feet long and 60 feet deep. Continuing along the paved road north west about 1.5 miles along we encounter an enormous ruin called Chetro Ketl, measuring roughly 320 feet by 450 feet deep. We are really getting excited and salivating over our detailed explorations over the next 4 days. Just a few minutes further the iconic monumental shape of the largest and most complex ruined city yet found in the US rises up between 3 and 4 stories high backed by a looming sandstone mesa; this ruined Pueblo cannot ever be mistaken for another Anasazi site, it is simply just too unique in architecture and grandeur to be anything but Pueblo Bonito, the Manhattan of the Ancient World in North America. This was supposed to be a simple recon, just a quick drive-through, however we just had to pull alongside the road to admire this impressive city. All right, enough is enough, we're getting anxious to set up camp, eat, and plan our next day's expeditions. On we drive for another half mile, and yet another behemoth ruin site, the walls of Pueblo Arroyo loom large and impressive. The road looping back towards the campground now, it is 0.7 miles to a grouping of 4 or more Anasazi structures to the south of our position called Casa Rinconada. Driving the 4.5 miles back to camp, we were in deep thought, completely unable to speak. Our first few hours at Chaco revealed far more than we could have every imagined simply reading publications or mapping from satellite imagery on the subject.

I backed the rig into our campsite, unlatched the roof retaining buckles, and Silverdunes raised the roof using the cranking handle. The entire raising the roof operation took about 30 seconds, this made easier by opening the rear ventilation hatch and opening the door so the vacuum would be broken. The sun was visibly lower, nearing 5 PM. The winds were really picking up now, estimating them at about 25 MPH steady from the southwest, and then temperature was dropping very rapidly from a daytime high of around 88F now to about 78F. The inside of Campy was registering 81F, so to conserve the heat in anticipation of a very cold night we left the windows shut. Some ominous looking clouds were gathering too. Appears that we will be in for some ugly weather overnight; perhaps a cold front!

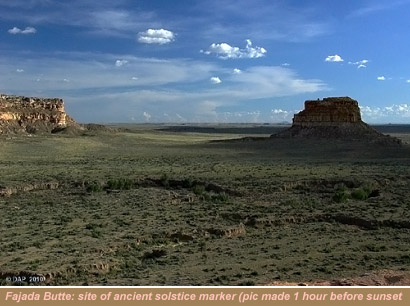

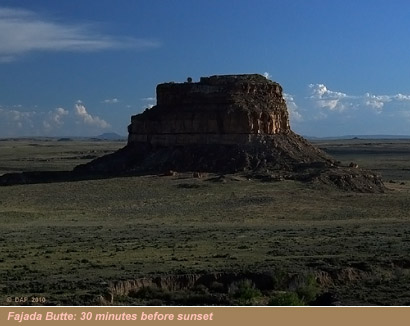

Rolling down every one of our 10 softwalled window blinds opened up a huge vista; we drank in the panorama. Red rock mesa and cliffs covering 180 degrees field of view to the front, and a wide open expanse encompassing at least 70 degrees field of view to our south and southwest; and at bearing 230 deg SW we could not quite see the top of Fajada Butte (upon which a complex of astronomical measurement tools are carved into the rock, during solstice and other events, a dagger pierces the spiral glyph during winter and summer solstices, and the equinox). With a bit of luck, we may see the star filled sky tonight. The Chaco Canyon is renowned for extremely clear night skies; the Park designating this sector as a critical natural resource to be protected, has an astronomical observatory on site and a structured program of night observation and lectures for Park visitors. We did not get the opportunity to visit the observatory during evening because of unusually heavy cloud and intermittent precipitation almost the entire time of our visit.

Hunger pangs were taking hold, so Dunes prepared a several course buffet meal of chili, burritos, party sausages and tacos, then later a desert of Powerbars. We talked about doing this kind of buffet in our old tent encampment set-up, and quickly dismissed it as nearly impossible requiring large counter space and various appliances, including a 3 burner stove. We were ecstatic with the camper and the decision to buy it and the 4x4 truck.

We took out our computer and opened it to the maps I had generated at home-office several months before we arrived here. We always prepare ourselves with the latest map data available, acquire all the State, Federal and topographic data layers, and assemble them well in advance of any of our expeditions. In the case of this Chaco expedition, we wanted to explore (remotely) the entire region's hypsographic (elevation data) and ecological information to get a feel for the Chaco region and the ancient civilization's ecological position within it. For a detailed write-up on how we did this, I urge you to please follow this link.

Essentially, this was my methodology and approach (however using space-based active SLR microwave sensor technology) to uncover undocumented ancient Mayan sites in Central America that led to some large on-the-ground discoveries back in the mid 1990s (see my one hour A & E Television documentary entitled: Lost Cities) Lost Cities of Central America: here

After going over our 3D model of the sector immediately surrounding Pueblo Bonito, we put together a plan of exploration for the following day: we would visit in order the Great Houses called Una Vida, Hungo Pavi, Chetro Ketl, Pueblo Bonito and finally Kin Kletso.

The wind was really howling outside by the time we turned in at around 10 PM. Extreme winds are common in this part of the Southwest during April and May. The sky was intermittently cloudy and clear, making star gazing a bit difficult. We used our thick down feather quilt and sleeping bags both that night. The camper rig was moving ever so slightly in the wind gusts lasting about 10 seconds every half minute or so. Thinking about what it would have been like to be an Anasazi occupant living in a sandstone block house among many other block houses throughout the Great Houses of Chaco we blanked out quickly.

Feedback: here

We snapped out of our deep sleep quickly the next morning from the bright early morning sunrise coming in through the cab-over bed's white opaque vent cover. We slept hard and deep. First thing on the agenda was making a liter of coffee using the French press (called a bodum). We could never understand why anyone would ever buy a single cup bodum when king-sized liter models were readily available. Boiling water in our IKEA kettle took about 8 minutes; we boiled enough water for both the liter of coffee and a sink full of breakfast dishes. All our dishwater and wash water went into a 12-gallon gray water tank under Campie, attached via a secured 4-foot drop hose. This handled tank was periodically dumped at the campground sewage dump site. Dunes whipped-up a nice fresh fruit salad, some hard-boiled eggs and some hot cereal. After doing the dishes, I headed outside with one of our 5 gallon flexible folding water containers in my hiking shorts for a swish off navy shower. It was still a bit cold at around 47F, but I needed a shower! Afterward, feeling refreshed, we packed our video and still photo equipment and tripod, threw in a good instant lunch and a liter of water each, collapsed Campie's roof in half a minute, and were off driving towards our 1st destination, Una Vida (or, One Life). None of these Great Houses were close to any of the undocumented sites and ancient roadways we had identified using air photo interpretation; we simply wanted to see first-hand as many of the Great Houses at Chaco humanly possible given our time-frame of visit.

Una Vida is one of the oldest Great Houses in the Chaco group at somewhere around 1100 years. Its structure is comprised of about 120+ rooms, and its structure is D-shaped (like Pueblo Bonito and others). This site is easily accessed from the Visitor's Center parking lot in a few minutes. The site is primarily rubble, with several stone walls protruding and gives a sense of what a site in dreadful condition looks like (by dreadful, I mean a site that has not weathered the elements well over the centuries; not from modern neglect).

We head out in the truck for our next site: Hungo Pavi, about 1.2 miles along the loop road. The name translates from Navajo as, Reed Spring Village. Quite visible from the road, the loop trail around what was a 4-story sandstone brick structure of 72 rooms, with one huge kiva, or circular ceremonial room, usually partly underground.

Next visited on our daily rounds was Chetro Ketl. According to my geospatial measurements (derived from high-resolution georeferenced imagery), the main complex making up Chtro Ketl is approximately 2.95 acres in size. One of the 2 largest Great House complexes in Chaco Canyon region, scholars estimate a minimum of 500 rooms, some of which occupied a 5th floor level. Dendrochronological investigations (tree-ring dating) place this Great House's occupation from architectural inception to abandonment at about 175-years. The kiva count is at a current 12. As a part of the ancient roadway system, one will find an ancient stairway behind the ruin traveling up to the mesa top. A bit east of Chetro are some substantial agricultural partitions, with evidence of irrigation canals and dam systems. With average annual rainfall in the Chaco region in the range of only 7 to 9 inches, it would have been imperative for the apparently relatively large and dense populations in this arid environment here to capture and distribute water whenever the opportunity arose. Chetro was the site of a large discovery of a cache comprised of several hundred painted wooden artifacts in the floor of one of its numerous rooms in the 1930s.

Easily visible at bearing 280deg W, just about 10 minutes along the National parks trail, is the immense Pueblo Bonito; the nexus of 7 primary Chacoan roadways, leading off like spokes of a wheel in nearly every cardinal direction towards other outlying ruin sites and Great Houses. As is often said: all roads lead to Chaco! Following up on this theme, several papers written in the 1970s about the Chacoan culture being an extension of the Aztec civilization far to the south, through a hand-full of connected artifacts, pose interesting possibilities. University of New Mexico researchers have recently published an analysis of organic cacao (or, in English, cocoa) residues found in several ceramic vessels retrieved from Pueblo Bonito (Crown and Hurst, 2008). Notwithstanding the copper bells and macaw remains found at Chaco, the new evidence of cocoa clearly cultivated in Mesoamerica being exported to the Chaco region for consumption during the 1000 to 1100 AD timeframe I believe is irrefutable evidence of strong trade ties. I cannot help but wonder if one of the purposes of the Chacoan roadway system, splaying out in literally all directions for tens, twenties and 50s of miles, like spokes coming out of a bicycle hub, was a way of attracting traders traveling up from Mesoamerica (the spider-web proposition)? Hence, all roads lead to Chaco. On the one hand, the Chacoan road system may have been used for purposes of ritual, purposes of transporting building materials, ancient Olympic-like games, and facilitating military offensive and defensive control; on the other hand, used for capturing wayward traders TO Chaco. As a note of interest, Fig. 3 adapted from Prufer K, Hurst WJ (2007) in the PNAS paper, entitled: The distribution of cacao cultivation in Central America and Mexico in A.D. 1502, relative to Chaco Canyon, missed indicating a large region of secondary production located around the Rio Paulaya, Rio Platano and Rio Patuca river valleys (P. House, ethnobotanical research in the Department of Gracias a Dios region of Honduras).

Pueblo Bonito, reported first seen and partially excavated by early American expeditions and explorer Lt. J H Simpson in 1849, lies within what is called the Chaco Complex of structures; its architecture appears to Dunes and I to be the pinnacle of design, layout and construction among all the Great Houses of a long past period known today as the Bonito Phase (notwithstanding the shoring up, re-mortaring and minor cosmetics it has received vis the other Great House structures). Again, According to my geospatial measurements, the main complex making up the D shaped Pueblo Bonito is approximately 2.88 acres in size; remarkably similar in spatial extent to Chetro Ketl-- Chetro Ketl appearing to be either a failed attempt at or perhaps competition among two building teams to build perfection in a D-shaped Pueblo design?

Speculation on its raison d'etre and the purpose of the hundreds of miles of fairly straight roadways emanating there-from vary from pure religious ceremonial facility; to a center of acquisition and redistribution of wealth through trade; to a highly centralized organized administration that had enormous influence over neighboring pueblos; to other iterations of centralized power, knowledge and influence. Speculation and research on the purpose of the ancient roadway systems varies from staging ancient Olympic Games runs; to military defense access right of ways; to highways allowing the transport of thousands of wooden lodgepole pine beams from forested regions to the north and northeast to construct the immense Great Houses; to marking a meridional linkage between other great pueblos far to the north and south (a meridian is a line of longitude from north to south, for positional purposes marked by intersecting points of longitude). Perhaps the reality lies somewhere within the elements of all the above?

An enormous archaeological undertaking ending in 1981 called the Chaco Project catalogued over 300,000 fragments of physical evidence of early life in the Chaco, and identified over 2500 building sites, however the question of why the ancient Chacoan road system was built may never be completely sorted out. Nonetheless every bit of new evidence our modest endeavor contributes to the puzzle could perhaps fill in some blanks and spark our speculative imagination on at least the extent of Anasazi/Chacoan occupation.

We hiked around the perimeter of sections of Pueblo Bonito to attempt visually to identify segments of ancient roadway (or, boundaries making up an ancient farming sector), however being directly on the ground has its observational disadvantages: it is nearly impossible to distinguish segments of roadways even when standing on top of them. This was pointed out to us while visiting an archaeological research project supervised by Dr John Kantner, at a Chaco outlier site near Casamero: John pointed out a segment of ancient roadway heading southeasterly. The road segment was extremely difficult to visualize even while standing directly on it.

Drifting dust, cattle movements, modern road-making over the decades has no doubt taken its toll on ancient roadway remnants. With this in mind, please refer to the remote sensed image thumbnail showing what I and Dunes believe to be segments of ancient roadway and/or farming field boundaries around Pueblo Bonito; as a note of interest the meridional alignment of the central wall inside Pueblo Bonito to roughly north can be seen in the map. Although it was not our intent to focus on Chacoan meridional allignments, using the Lekson longitudinal Chaco center coordinate to generate a line of longitude for our map (see Viewshed Map, in side bar) and measuring its proximity to near-by sites (strikingly, Tsin Kletsin and Pueblo Alto) proved interesting. The distance from northwest corner of Pueblo Alto structure to Center Meridian is 30 meters (this may vary by a half meter either way), and the distance from the same meridian to the northwest corner of Tsin Kletsin (about 3.7 kilometers distant!) is 29.1 meters (this may vary by a half meter either way). It appears that both the Pueblo Alto and Tsin Kletsin west-facing walls are parallel to the meridional line; this in itself I think is not significant, however the constructing of two Chacoan structures, both among the highest situated altitudinally, within a meter of the same meridional longitude is a remarkably note-worthy accomplishment to say the least. In my viewshed analysis from the perspective of a viewer 3-meters obove the ground (see Viewshed Map in side-bar), the miniscule visible terrain patch within which Penasco Blanco resides allowing line-of-sight from Tsin Kletsin may be coincidence. However, all three significant high-altitude sites may have been scoped-out by Chacoan builders because they are all visible from at least the perspective of Tsin Kletsin. To say that either planning or random chance are responsible for these site locations would be a tough call.

It was getting late in the day; the temperature was registering about 84F. We packed it in, hiking back to the camper, we then drove back to camp. Backing the rig in and setting up took about 5 minutes. We checked our marker tent and its belongings, and hauled out a gallon of cooking water. We differentiate between cooking/drinking water and washing water thus: any water we acquire from taps and water sources at campsites like Chaco is put in special 6 gallon colored containers and poured into Campy's fresh water tank, and used only for dish-washing and showering. Water we have acquired from a trusted source is kept in white opaque single gallon and five gallon containers, all separately stored. Supper was made, and we got down to the business of discussing the day's observations.

At roughly 8 PM we observed quite the blackened sky to the south. We surmised that some kind of precipitation was heading our way, and it seemed that this storm would be unavoidable. The first waves of wind-driven sand particles started pinging off the side of Campy, and before too long a decent rain hit us. Pelted by intermittent rain and sand particles, we secured Campie by packing dampened paper towels into the weeping holes at the bottom channeling of our large windows; this to keep out the sand and dust. I brought down the roof vent hatches, and we opened the lights in the camper. The wind and intermittent rains went on for over an hour, so we decided to hit the sack, and read till we fell asleep.

Awakening early the following brilliantly-sunny morning to a crisp chill, we prepared coffee, and a hardy breakfast on the 3-burner Suburban stove-top, and reviewed our plan for the day: driving to and past Pueblo Bonito to the last parking section, then hiking to Pueblo Arroyo; then trekking to Kin Kletso; then a trek to Casa Chequita (the farthest site west we will visit); then back to Kin Kletso to the Pueblo Alto Trail; intersect with our first ancient mesa-top road segment; intersect with Pueblo Alto ancient road segment; then to Pueblo Bonito overlook; back down the Pueblo Alto Trail to Campie and a drive to our last stop of the day, the sprawling Casa Rinconada site. This will be one of our longest trekking days with over 10 miles of hiking including a mesa climb.

Our primary objective is to attempt to locate ancient roads segments we (or, what we think we have) identified using remote-sensing interpretation (analyzing high-resolution imagery product and establish from said probable/potential ancient road segments).

From the end of the visitor road parking area to Pueblo del Arroyo, it took us just minutes to traverse the quarter mile and arrive at the first structures and kivas. Pueblo del Arroyo translates: town of the gully. This is also the access to the back country trail leading to the South Mesa (about 2.7 miles one way, back country permit required) and other identified ancient road segments heading southwest. This visit, we will not explore this sector. Up till this point, we have not traversed the terrain where prominent archaeological features were interpreted from the heads-up digitized NAIP imagery (see previous explanation above).

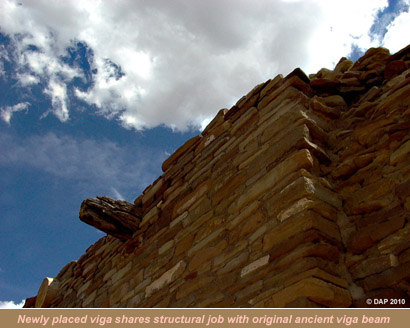

The item that attracted us most at this particular site were the huge beams used in building these gray-brown stone Great Houses, mortared with a mix of clay, silt and water. The exposed vigas, or beams, were of fairly straight ponderosa pine, and were one of the sources of the dendrochronologic dating (tree ring dating) that placed the construction time-line of these structures at about 1059 to 1124 AD. Fire-pit dating puts the residual ash as recent as 1178 AD remarkably (Bannister, 1953). Tree ring research has also revealed that in the region where the trees were harvested, almost no climatic change has taken place since the region had been built upon. One of the prominent structures at Arroyo is the enormous 70-foot diameter kiva.

After making 20 minutes of digital video footage of our trek through Pueblo del Arroyo, and shooting macro photographs of the most prominent vigas, we trek west-north-west 0.3 miles to our next destination: Kin Kletso.

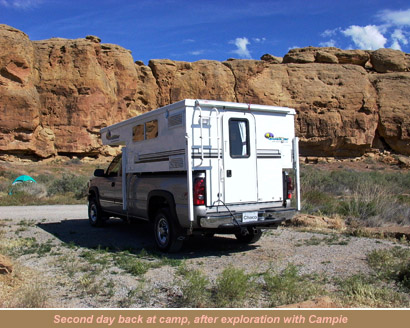

Kin Kletso, or Yellow House had approximately 50 plus rooms at 0.2 acres in area; studies show that perhaps only one family occupied this Great House. Its walls are remarkably well reconstructed from very light-colored sandstone and quite high. The earliest excavations here took place from the 1920s to 1930s. Kin Kletso is also the start of our climb up to the mesa top, where we can get a birds-eye view of Kletso, Pueblo Bonito and any ancient road segments surrounding Pueblo Bonito, and far our through the Southern Gap.

The trailhead is directly behind Kin Kletso, and winds its way up towards the mesa cliff face, and enters a massive crevasse, where a steep climb awaits. Once you break the top of the crevasse, the terrain levels out onto the slick-rock. This crevasse is in all likelihood the same route that the ancient Anasazi used to access the lower Pueblos and upper mesa; in fact, it is the most evident of an ancient roadway-trail system we will see on this expedition! Please view our climb video linked below:

Mesa top climb:

The cliff-top trail is marked only with small rock cairns, so we must really keep a look-out for them. We are searching at this point for our second ancient roadway segment according to our GPS coordinates (derived from our air photo interpretation of ancient Chacoan roadways segments) at: location A on this map. On the ground we are looking for a change in vegetation type or a higher vegetation density when compared to the surroundings. Changes in terrain, like built up berms, man-made elevations and ramps are also indicators of ancient road segments. Standing directly on top of the end of a road segment as identified on our high-resolution aerial imagery is no guarantee of our being able to identify it at eye-level on the ground, for sure. We look in the bearing and direction that the road segment is supposed to travel and no visual distinction can be made from surrounding terrain!

This experiment is proving interesting. Remote sensing using high altitude imagery seems to be the best ancient roadway identification method; however on the ground invasive excavations need to be done to attempt to reveal a road bed profile (this of course is illegal in a National Park without written permissions). Onward we push to our next ancient roadway segment: location B on this map. We arrive at the juncture of one of the start of one of the longest road segments we have identified: this road segment leads directly up-slope to Pueblo Alto, nearly a mile to the north east. From here it is only a few hundred yards to the Pueblo Bonito outlook. This section of the roadway is made up intermittently by slickrock, loose gravel, dust and small boulders. We think we can see some vague berm in several sections, however identifying it visually definitively is proving to be rather tough. We timed this last leg of our trek on day 3 to coincide with late afternoon light to afford a better contrast when scrutinizing the terrain for man-made structures.

With about 2 hours of time left till CCNHP closing, we head down the Pueblo Bonito overlook trail to a point we know from our 3D terrain map that will afford us an unobstructed view between South and West Mesas (the South Gap), bisected by what we have identified as being an ancient road segment. We set up our digital video camera with telephoto lens attachment, fit a circular polarizer over the lens, mount the camera to a Sherpa tripod (very heavy sturdy tripod weighing 7 pounds), fire it up, set manual lens parameters and have a look. Wow, cool. Being aware of the contemporary man-made road, we discount this and focus in on what appears to be a very long Chacoan road segment heading south-southwest. The wind was steadily picking up in strength, and the wind screen over the large microphone was not able to subdue the wind popping and roaring in my headphone monitor, however the tripod held steady and we could quite clearly extract what appeared to be the ancient road segment by rotating the polarizer filter. Please view our ancient roadways video linked below:

Ancient roadways:

This is what makes our expeditions so exciting; building up geographical models many thousands of miles away a year in advance with the latest geo-spatial data, and doing the expedition to proof whatever remnants of ancient civilization we had detected remotely, directly on the ground!

We have just enough time to do a trek to Casa Chequita; the farthest site west we will visit this day. Before we left the Pueblo Bonito lookout, we had one more photograph to make: we could see Campie clearly way off in the distance below in the parking area (see photo).

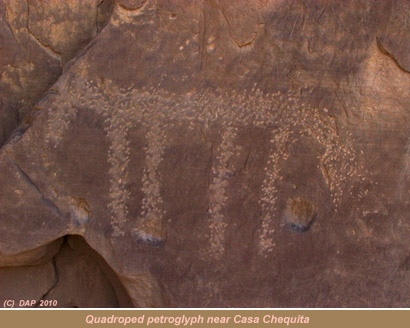

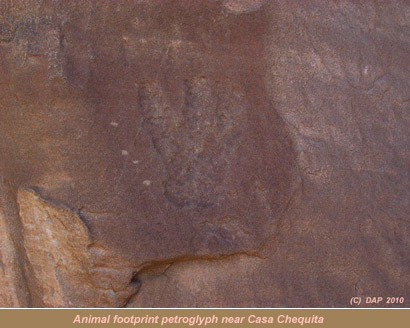

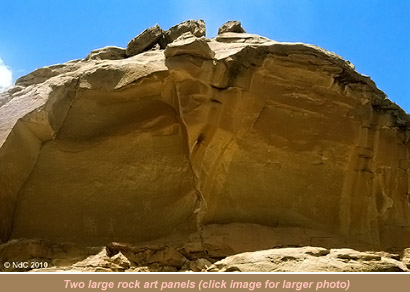

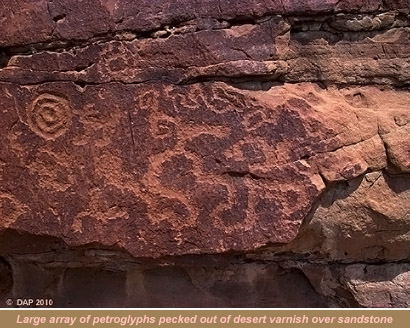

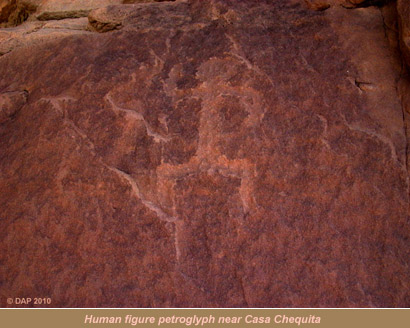

Back-tracking down the Pueblo Bonito lookout trail through the crevasse, and past Kin Kletso, we hit the trail for Casa Chequita, or the Little House, and the petroglyphs there around. This trail segment is about 0.7 miles of undulating hills, crossing a prominent wash. Arriving at the petroglyph panels, we photograph 11 distinct panel sections depicting what appear to be an impression of a human foot (replete with 4 toes), a large bird foot bas relief (3 toed), numerous spirals, several geometric shapes, anthropomorphs and a group of humans. Dunes has been fascinated by petroglyphs and pictographs (painted rock art) since first visiting the Southwest over a decade ago. Her interest specifically in rock art are the recurrent themes and cardinal orientations (celestial veneration) found in different regions once occupied by the Anasazi, Fremont, Mogolon and other ancient cultures throughout Utah, Colorado, New Mexico and Arizona. Her interest in recording and cataloging ancient rock art has brought us as far as Minnesota and northern Ontario and southeastern Quebec, Canada. Specific recurrent themes she has found throughout the southwest are the various spiral incarnations, several proven by researchers to be an intrinsic part of measuring the on-coming seasonal changes (the solstices, as an example, as measured by the installations on Fajada Butte, and at Wijiji in the Chaco region).

We take one last look out towards the mesa-top Great House of Penasco Blanco as the sun drops, make a photograph of the western canyon, and promise ourselves a future visit out to that last far-flung Pueblo roughly 6 mile return trek from Casa Chequita. The shadows being thrown by the setting sun on the canyon walls is indescribable. We appear to be the only visitors left in this sector of the Park; approaching Campie sitting alone in the parking area, we are the last visitors out here. The wind has dies down substantially, and only sounds of the meadowlark are audible. I wonder what it had been like living here during 1050 AD ? Perhaps flute players sitting atop to mesas and in alcoves playing unimaginably different sonatas as Pueblo dwellers walk to and from sectioned gardens, listening to the music reflected acoustically off the opposing canyon walls? Or, could there have been anxiety and worry over potential raids from distant tribes picking off the Chacoan outlier settlements during the rainy season?

Back at camp, we download photos and video footage to our computer, and make extensive notes on our day's findings while munching on Powerbars. Having washed off, had supper and set up the campfire, we caught glimpses of the brilliant stars between fast-moving clouds. Temperatures dropped very quickly after 9 PM, and at about 50F we put out the fire, head into Campie, make a tea and read by the marine battery-powered lighting, nodding off around 10 PM.

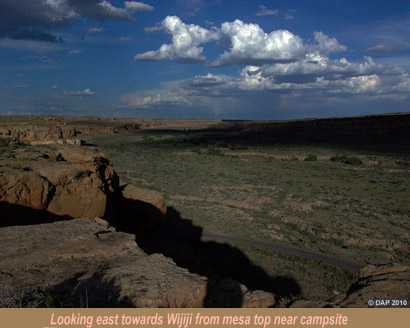

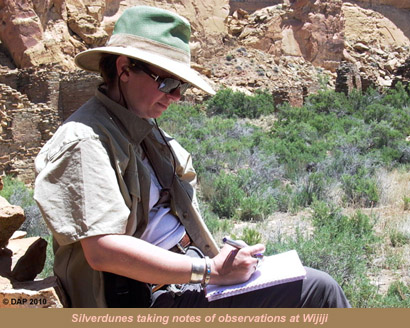

Blazing sunshine happening and a half-liter of French-roast coffee in hand on this our fourth and last day at Chaco, we go over our detailed plans for our most exciting trek: Chacoan Great House Wijiji (translates from Navajo as greasewood). We would leave Campie at the campground and walk to Wijiji from here. This site appeals to us for several reasons: its highly symmetrical architecture; modest restoration work having been done; its location related to a distant mesa notch where the sun rises during the winter solstice; and its apparent relative anonymity when it comes to Park visitors. During our treks around the more well-known Pueblos of Chaco, we were seldom alone; however out at the distant Wijiji, we passed not a single visitor coming, while there, and returning! Spending from morning to late afternoon here, this was quite something. We shot at least 2 hours of digital video here, recording the views from 12 bearings, through windows, through doors, of song birds, insects, wall segments and our musings and ramblings on Wijiji from perspectives of archaeoastronomy, archaeology, pre-historical geography, paleoclimatology and other fields of specialization.

Wijiji was only the second opportunity we had in the Chaco to shed our connection with modern civilization, stake a comfortable place to sit, and meditate on our surroundings for hours at a time. This fairly distant Great House seemed to be out on the periphery of what would have been a fairly densely populated and busy central Chaco (similar to Penasco Blanco in distance from central Pueblo). What could this site have been used for? Because of its distance from central Pueblo, it must have had perhaps a significant reverence for the Chacoan civilization, and when this locale is thought of in concert with yet another sun cutting through spiral petroglyph (located at the mesa behind this site), it may have been a back-up to the Fajada Butte sun dagger?

Finishing up my filming and photographing of Wijiji, Dunes packed up her drawing utensils and we slowly drifted back in the direction of our campsite. Our entire Wijiji expedition rounded out to 5-miles; in fact the return trip from the campground is 3 miles, however we walked an additional 2 miles around Wijiji environs looking for less documented sites and enjoying the freedom and tranquility of this sector of Chaco.

On arrival back at Campie, we ate a light snack and I packed a light backpack with Leica camera, my polarizer filter and tripod for a solo trek to the top of the mesa surrounding the campsite just before sun-down. Dunes and I carry several radios: an FRS radio set back-up, and a GMRS radio primary system. In an open desert environment like the Chaco, we typically can communicate over about 14 miles with the GMRS set, and about 3 miles with the FRS set-up. I packed the FRS radio as a safety, in case of snake-bite or physical injury while trekking solo because there was no need for the more powerful GMRS system. I left Dunes doing drawings in the shade of Campie's giant Flying-V awning, and headed directly up the mesa side to the mesa top on a trail near the campground dump station. In addition to the pocket GPS, I carry a solid steel sighting compass to take bearings with as I head across country, making note of the prominent high points as I trek. My goal was to circle around the Gallo tent site mesa, eventually to a point directly above our camper (no trail here); here I planned to make photos of the campground and Campie from 100+ feet above.

I had my sticky-soled rock scrambling shoes on, and leapt across several crevasses saving me perhaps 0.2 miles of wide-tracking. I pretended that I was living vicariously through the eyes of an Anasazi runner, clandestinely scouting out a distant Pueblo unbeknownst to the population. I hugged the edge of the cliff around the campground, and saw campers going about their chores around their tents far below; no one had any clue that I was way, way up there. Around I went, and off across 0.1 miles of slickrock; I took several bearings, and headed in a straight line to where I calculated the rim edge would be above our campsite. I got closer to the sheer cliff edge, had a look-see, and yes, I was about 40-feet long off my mark; walking a few meters back I positioned myself so Dunes could see me, and called her on the FRS radio. In seconds she was waving to me from far below. I made a few photos of Campie and the general campground layout, and headed back in the same direction for my next destination: the lookout on the mesa top side facing Fajada Butte.

The sun was markedly lower by this point, however I scrambled back across the 5 crevasses, and took a bearing that would intersect with the original trail. In about 10 minutes I encountered the marked foot trail, and headed off half jogging towards Fajada Butte. I took another bearing due south, and broke the trail across slickrock towards what would be the edge of the mesa top, and in 2 minutes was there. I followed the edge of the mesa in an attempt to get a better perspective of Fajada Butte. The sun was now perhaps 30-minutes from setting; it was getting noticeably dark so I had to move fast. I tried the FRS radio, however I appeared to be out of range (may have been the altitude and million-ton mesa in the way!). I jogged another 5 minutes, found a perch, set up my camera gear, attached the appropriate filter, and concentrated on the last minutes of the sun, its light, where its shadows were traveling, the clouds' shadows casting onto the canyon floor; making a dozen mental calculations a minute, squeezing off 3 auto-bracket photos a second. I shoot up canyon, down canyon, cross canyon and various exposures of Fajada itself.

With what I calculate to be about 15 minutes to sunset, I fast packed all my gear, and headed back at a medium jog while I could still see the ground in front of me. The temperature was really dropping; I'd guess to about 55F by now. I took bearings on several prominent boulders I had memorized on the way in; eventually, I intersected with the actual trail, and trying the FRS radio, I was able to make contact with Dunes. Hiking down the last 100-meter stretch of trail to the campsite a few minutes after sunset, I make the campground.

In retrospect we perhaps could have stayed at Chaco several additional days; we really would have liked to have made it to Penasco Blanco, and even Kin Klizhin! We had already trekked out to several Chaco outlier sites with the jeep, including Kin Bineola, so rounding off our explorations with the near-in outliers would have really made our week. Our interest in Kin Bineola was from a very long ancient Chacoan road segment I believed I had identified through remote-sensed imagery. Getting out there was a fairly difficult expedition in itself; we made a longitudinal crossing along a 10-foot high, 7-foot wide earthen dam. The temperatures at Kin Bineola at time of arrival was 101F. The pull of Chaco is again strong; we will be back, and will perhaps stay for several weeks.

--END--

Bibliographic references and further reading:

Crown, L. Patricia and Hurst, W. Jeffrey. Evidence of cacao use in the Prehispanic American Southwest. PNAS. 2009. vol. 106. No. 7.

www.wlbcenter.org/drawer/journalclub/PNAS-2009-Crown-2110-3.pdfKantner, John. 1997 Ancient Roads, Modern Mapping. Evaluating Chaco Anasazi Roadways Using GIS Technology. Expedition 39(3):49-62.

Lekson, H. Stephen. The Chaco Meridian, Centers of Political Power in the Ancient Southwest. 1999. AltaMira Press. Walnut Creek, CA.

Schaafsma , Polly. Rock art in New Mexico. 1992. Museum of New Mexico Press, Santa Fe, NM.

Vivian, R. Gordon. 1934a. Final Report, Archeological Reconnaissance under Civil Works to February 15, 1934. National Park Service, Washington, D.C., and Chaco Culture National Historical Park.

Vivian, R. Gwinn and Buettner, R. C. 1975. Wooden Ritual Artifacts from Chaco Canyon, New Mexico. The Chetro Ketl Collection. Submitted in fulfillment of Contract 4940P21004. Chaco Archive 2017, NPS Chaco Culture NHP Museum Archive, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. Published in 1978.

Wagner, D., In Trombold, C. (Ed.) Analysis of Prehistoric Roadways in Chaco Canyon Using Remotely Sensed Digital Data. Ancient Road Networks and Settlement Hierarchies in the New World. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1991.

some cool maps we used and actually designed and created for this journey

Feedback: here